I once struggled with bonding a cooling plate and the joint failed prematurely—this problem hit hard when time and cost were on the line.

A proper surface finish ensures good bond strength, long‑term durability and reliable heat transfer for a liquid‐cooling plate assembly.

I’ll walk through what surface finish means in bonding, why roughness matters, how to choose a finish for a liquid cooling plate, and what new methods are optimizing surface prep.

What is “surface finish” in bonding?

Imagine gluing two plates together but the surfaces don’t truly meet—little peaks and valleys block contact and weaken the bond.

Surface finish refers to the micro‐texture (roughness, waviness, lay) and condition of a substrate’s surface that affects how well an adhesive or bonding method works.

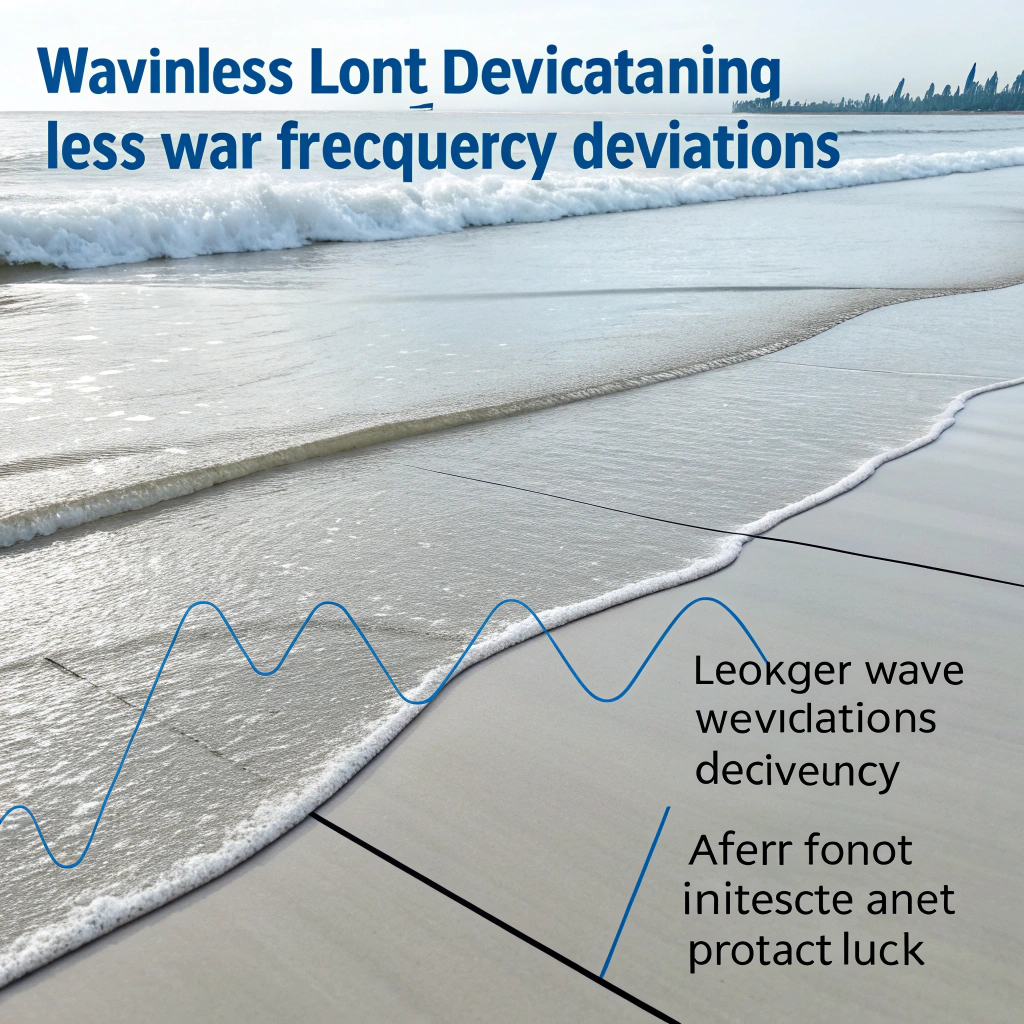

In bonding technology the term “surface finish” encompasses more than just how smooth or shiny a surface appears. It includes characteristics such as roughness (small deviations from an ideal smooth surface), waviness (longer‐wave deviations), and the lay or pattern direction of the surface texture.

When I bond a liquid cooling plate (e.g., an aluminium plate for coolant‑flow channels), the adhesive must cover the bonding area, wet the surface, and cure such that mechanical interlocking and adhesive interface both are effective. For that to happen the surface finish must be appropriate: too smooth and the adhesive may not “key” into the surface; too rough and the adhesive may not fill all gaps, leaving voids or air pockets. For example, as the coating on the surface deteriorates or contamination remains, the adhesive may only bond to contaminants instead of the substrate itself.

Also important is the concept of surface energy—the readiness of a surface to be wetted by a liquid (adhesive) is influenced by the chemistry of the outermost layer. If a surface has low energy (for example a polymer coating, or oily film) the adhesive may bead up rather than spread and make intimate contact.

In table form:

| Parameter | Definition | Why it matters for bonding |

|---|---|---|

| Surface roughness | Small height deviations from nominal surface | Affects the contact area and mechanical interlock |

| Waviness | Longer wave deviations (less frequent, larger scale) | Can influence uniformity of adhesive layer |

| Lay / texture pattern | Directional pattern from machining, extrusion, etc. | Affects flow of adhesive, anisotropy of bonding |

| Surface energy | Chemical / physical readiness to bond or wet surface | Governs adhesive spreading, chemical adhesion |

| Cleanliness | Presence or absence of contaminants | Contaminants weaken bond interface |

[claim claim="Surface finish only refers to how smooth the surface looks." istrue="false" explanation="Surface finish includes roughness, waviness, lay, and chemical condition—not just visual smoothness." ]

[claim claim="Good bonding requires a surface with adequate roughness and high surface energy." istrue="true" explanation="Both physical texture and chemical condition must support adhesive wetting and mechanical lock." ]

Why does surface roughness affect adhesion?

One look at a microscope reveals that what seemed smooth is full of valleys and peaks—these features change how an adhesive behaves.

Surface roughness influences adhesion because it changes contact area, enables mechanical interlocking, but too much roughness may hinder adhesive flow and trap voids.

Let me explain the mechanisms. There are two major ways bonding works: mechanical interlocking and chemical/adhesive contact. When you roughen a surface, you create more surface area, more asperities (peaks & valleys) which the adhesive can “grab” onto. Also, the irregular surface may slow crack propagation at the adhesive interface, improving fatigue performance.

However, there are trade‑offs. If the surface is too rough, the adhesive may struggle to flow into all the valleys, leaving voids, air pockets, or inconsistent wetting. That reduces the actual contact area and can even act as stress concentrators.

Another key point: even if the roughness is ideal, if the surface is contaminated the adhesive will bond poorly. I once saw a part that had been blasted (so roughness was high) but remained oily and the bond failed because there was no chemical adhesion and limited wetting.

So you can think of this interplay:

- Roughness ↑ → potential for better mechanical interlock and larger area

- But cleaning, surface energy, adhesive viscosity + flow characteristics must match

- Excess roughness or inappropriate adhesive/viscosity mismatch → gaps, voids, weaker bond

From a practical perspective for bonding a cooling plate, I look at the adhesive type (liquid epoxy, gap‑filling adhesive, structural adhesive) and ask: Can it wet the surface being prepared, flow into irregularities, cure without shrinkage creating voids? And what roughness range gives the best compromise? Some guidelines for metals (general bonding) suggest an RMS around 150‑250 micro‑inches (≈3.8‑6.4 µm) for metals prior to bonding.

[claim claim="Increasing surface roughness always improves bonding strength." istrue="false" explanation="Beyond a certain point roughness becomes excessive, prevents proper wetting/flow of adhesive and can reduce bond strength." ]

[claim claim="Removing contaminants and increasing surface energy is as important as roughening the surface." istrue="true" explanation="Even a perfectly rough surface without clean, high‐energy condition will lead to weak bonding." ]

How to choose surface finish for bonding a liquid cooling plate?

When I designed a bonded aluminium cooling plate, I had to pick the surface finish based on adhesive, metallurgy, environment, and thermal goals.

Choosing the right surface finish for bonding a liquid cooling plate involves matching roughness and cleanliness to the adhesive’s flow/viscosity, substrate material, thermal/structural load and environment.

In the specific context of bonding a liquid cooling plate (for example aluminium plate with coolant channels bonded or adhered to a component or cover), here are the steps I follow and considerations I use.

1. Identify the substrate materials and adhesive

If you have aluminium alloy (e.g., 6061‐T6 or 6063‐T5) on aluminium or aluminium on composite, the surface finish requirements differ compared to bonding steel to composite. Also check the adhesive: is it a structural epoxy, gap‑filling adhesive, silicone, etc.? The adhesive’s viscosity and ability to fill gaps influence what finish is acceptable.

2. Determine required joint performance and environment

If the cooling plate will experience thermal cycling, vibration, fatigue, fluid exposure, then the bond must resist peel, shear, fatigue, corrosion. That suggests a finish that supports good mechanical interlock and chemical adhesion, but also avoids features that trap moisture or degrade over time.

3. Specify a roughness target and surface prep method

For an aluminium cooling plate bonded with structural adhesive, I might specify a finish in the Ra ≈ 2‑6 µm range depending on adhesive gap fill. Also I check the lay direction — if the adhesive is applied in one direction I might ensure the roughness lay does not impede flow of adhesive during application.

4. Ensure surface energy and cleanliness

Regardless of roughness, if the aluminium has an oxide layer, release agent, oil film or contamination the bond will weaken. So the finishing steps must include degreasing, oxide removal or appropriate conversion treatment, rinsing, and verifying wettability.

5. Choose consistent surface finish across mating faces

Ensure both surfaces are prepared with consistent finish so that the adhesive layer is uniform, thickness controlled and voids minimised.

6. Consider post‐surface‐prep handling and storage

Even if you roughen and clean the surface, exposure to environment, handling, storage can degrade surface energy. Control the time between surface prep and bonding.

| Factor | Low roughness finish | Higher roughness finish | Which to choose? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesive viscosity/flow | Needs smoother finish | Can support more interlock | Choose based on adhesive capability |

| Thermal interface requirement | Prefers smoother | Rough finish may increase resistance | If thermal conduction is critical → smoother |

| Mechanical fatigue / vibration | Moderate roughness OK | More interlock beneficial | If high loads → moderate roughness |

| Surface cleanliness risk | Easier to clean thoroughly | Traps contaminants | If cleanliness critical → smoother finish |

[claim claim="If the adhesive has high viscosity and gap‑filling ability, you can allow a rougher substrate finish." istrue="true" explanation="High viscosity adhesives can fill larger surface cavities, hence rougher surfaces can be tolerated." ]

[claim claim="A mirror‐polished surface always gives the best bond strength." istrue="false" explanation="A mirror finish may lack mechanical interlock and may reduce adhesive wetting if the adhesive cannot flow into any minute defects." ]

What new methods optimise surface preparation?

In recent years I have seen laser cleaning, plasma treatment, chemical functionalisation applied to bonding surfaces—these methods go beyond traditional sand‑blasting.

Modern surface preparation methods—such as laser texturing, plasma cleaning/activation, and chemical etching—are enabling improved bond reliability, faster cycle times and better surface energy control.

Let’s examine some of the modern approaches and how they apply to bonding of cooling plates (or other bonded joints) and why they matter.

Laser cleaning & laser texturing

Laser treatment can remove contaminants and simultaneously texture the surface at micro‑scale, increasing surface energy and roughness in a controlled way.

Plasma, corona or flame treatments

These treatments activate the surface chemically without greatly altering roughness. They remove contaminants and increase surface energy, improving wettability.

Chemical etching / conversion coatings

Chemical surface modification such as phosphoric acid etch or anodising creates microporous layers that adhesives bond well with.

Hybrid and inline automated surface prep

Inline robotic systems using plasma, laser, or micro-blasting ensure repeatable prep in high-volume lines.

Surface finish measurement and verification improvements

Modern tools now quantify wettability and roughness precisely—contact angle tests and profilometers ensure every surface is bonding-ready.

[claim claim="Plasma treatment improves bonding mostly by altering surface chemistry, rather than significantly changing surface roughness." istrue="true" explanation="Plasma treatments typically increase surface energy and functional groups, not large changes in macro‑roughness." ]

[claim claim="Laser roughening always replaces the need for cleaning step." istrue="false" explanation="Laser roughening may remove contaminants but cleaning is still required to remove oils, residues, handling films to ensure the surface is fully receptive." ]